As any regulars will know, I’ve been looking into ADHD as one of my key neurodivergent traits but, more recently, I have come to realise that its not quite as simple as that (and with me, it never is). Having come across the concept of “twice-exceptional” or “2E”, I find this fits me like a glove where ADHD alone feels more like a mitten, as in, it loosely applies but there are areas where it doesn’t even touch the side of my complexities. Having spent quite a number of days hyperfocusing on the topic of adult 2E (there is far more information out there relating to children than adults but, thankfully, there are also grassroots websites, forums and podcasts starting to appear…) I am now convinced this is “me”, as it feels like the biggest missing piece of my jigaw puzzle so far. And, by the way, tenaciously seeking answers to the “puzzle” of ourselves (when most people have far less interest or concern to get to the bottom of their own quirky neurobiology…) is an extremely “2E” thing to do…and the raison d’être for this longstanding blog so, already, I see that I am living according to type!

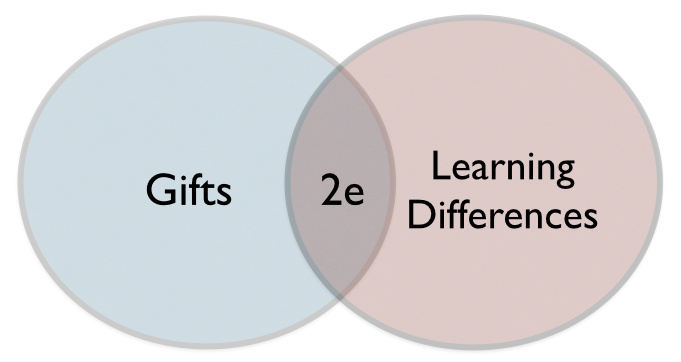

So what is 2E? In a nutshell, it refers to a situation where “deficits” (really, differences, such as autism, ADHD etc which make life generally harder for an individual as compared to someone that is neurotypical) lie side-by-side with “giftedness”. There, in that one word “gifted”, lies a major stumbling block to individuals realising they or their child are 2E…in fact, there are potentially two tripwires. One is that our idea of what constitutes giftedness is just so limited and far off the mark. People tend to think of that child piano prodigy or the one that is doing college-level maths at the age of seven yet, by limiting their concept of what giftedness looks like to something so academic or performance oriented or, in short, an “extraordinary achievement” model of giftedness, they are missing the point (and a lot of other presentations of it, see below). The other is an active aversion to the very concept of being gifted in our society, which I will enlarge upon below but what it boils down to is the assumption that the gifted are some sort of “elite” when, in reality, they may present as individuals who feel lost, isolated and quite unseen and unsupported by our culture with its narrow criteria of assessment.

For those of us growing up 20+ years ago, there simply weren’t the gifted programs available to determine whether we were “gifted” as there (sometimes) are in modern schooling. Where the concept of giftedness is applied, even today, it tends to refer to academic criteria such as IQ assessment rather than looking at a broader picture of traits (see what some of those gifted traits may look like below). Also, as it stands, society only tends to measures giftedness in terms of what we “achieve” or “do with” said gifts, meaning other forms of giftedness that are harder to measure against neurotypical performance or skills, particularly those outcomes of giftedness that do not conform to outcomes, targets, agendas and goals that are most valued by a specifically neurotypical society, simply go unnoticed and unvalued. Not all gifted individuals are neurodiverse (of course) but, for those that are, being noticed as gifted becomes doubly hard since they are not always gifted in ways that are obvious or culturally valued.

Most important to consider is that, out of 10% of the population that are gifted (based on the definition of the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) which defines gifted individuals as “those who demonstrate outstanding levels of aptutude (defined as exceptional ability to read or learn) or competence (documented performance or achievement in the top 10% or rarer) in one or more domains”) not all will be academically gifted, and perhaps this is even more likely for those who class as neurodiverse. To quote neuroscientist Nicole A. Tetreault (Insight Into a Bright Mind: A Neuroscientist’s Personal Stories of Unique Thinking) “Gifted diversity begins with the brain, and a different experiencing of the world. In particular, gifted individuals are “hardwired” differently. Their differences encompass brain anatomy, bodily perceiving, sensorary processing, levels of intensity, increased sensitivities to bodily sensations, emotional intelligence, and elevated responses to the environment”. How many of these get picked up on, or are valued, by our schools? She continues “When the range of possibilities for gifted individuals to fit in is narrow, and their giftedness is limited to education, achievement, and success, they may not be able to cultivate true meaning and integrate all the facets of their personality, and therefore not meet all their social, emotional, mental, intellectual, creative, physical, and sensory needs”. If this feels like you or someone you care about, read on…

Let’s take a moment, here, to consider some of the signs that an individual is gifted (taken from Lynne Azpeitia’s website Gifted, Talented and Creative Adults which draws on “Gifted Adults: Their Characteristics and Emotions” by Annemarie Roeper (go to her Lynne’s website for reading recommendations and further articles).

Gifted adults differ intellectually from others and are more sophisticated, more global thinkers who have the capacity to generalise and to see the complex relationships in the world.

Gifted adults have a heightened capacity to appreciate the beauty and the wonderment in our universe. They deeply experience the richness of the world and see beauty in human relations, nature, literature.

Gifted adults crave interchanging ideas with other gifted adults and many love to engage in intense intellectual discussions.

Gifted adults have an inner urge to fulfil their own expectations and feel very guilty if they cannot even when no one else sees the need to.

One of the most outstanding features of gifted adults is their sense of humour which differs from others and consists often of subtle jokes, intricate teasing or puns. Gifted people often find that their jokes are received with silence because they are not understood.

Gifted adults often have strong feelings encompassing many areas of life and have difficulty understanding the seemingly inconsistent and shortsighted behaviour of others because they can see the foolishness, unfairness and danger of many actions in public and personal life.

Gifted adults have a special problem awareness. They have the ability to predict consequences, see relationships, and foresee problems which are likely to occur.

Because gifted adults know more what is at stake, risk taking for a gifted person may be more difficult than for others because it may take longer for them to decide.

Gifted adults often develop their own method of learning and grasping concepts which can lead to conflict with others who don’t use or understand their method.

Gifted adults have normal feelings of anxiety, inadequacies and personal needs. They struggle to have these needs met and taken care of just like all human beings do.

Gifted adults are often confronted with the problem of having too many abilities in too many areas in which they would like to work, discover and excel.

Gifted adults are often driven by their giftedness and may be overwhelmed by the pressure of their creativity. Giftedness is a drive, an energy , a necessity to act—it’s a need for mastery, intellectually, creatively, and physically which grows from the need to make sense of the world, to understand the world and to create one’s world.

Gifted adults need time for inner life experiences, and to understand themselves. Because it takes quiet time to clarify thoughts and feelings, gifted adults need contemplation, solitude and daydreaming.

Gifted adults relate best to others who share their interests.

Gifted adults may have a small circle of friends or sometimes only one, but the relationships are meaningful.

Gifted adults are independent thinkers who do not just automatically accept the decisions of their supervisors. They function well in a participatory community and with those who are accepting of their attitudes and innovations.

Gifted adults have strong moral convictions and many use their specific talents, insights and knowledge for the betterment of the world.

Gifted adults have an understanding of the complexities and interrelatedness of global affairs and have the capacity to replace shortsighted, short-term reactions with careful overall solutions

From Characteristics of Gifted and Creative Adults.

If you relate to many, or all, of these as I did you may well be gifted. Another useful source of information on this topic is psychotherapist Paula Prober (website: Your Rainforest Mind) who favours that term “Rainforest Mind” rather than 2E. To give you a flavour, she describes this as “intense, multilayered, colourful, creative, overwhelming, highly sensitive, complex, idealistic, and influential” yet often “misunderstood, misdiagnosed, and mysterious” and, “like the rain forest”likely to have ”met too many chainsaws”. For her full description of such a mind’s many characteristics, go to her website or read her book.

So, as you can see, the fuller picture of what constitutes giftedness is so much more than the very narrow idea we think has something to do with a person’s IQ score or academic performance compared to peers and this is that first stumbling block on the way to being identified as such. So, yes, I came across the term twice-exceptional once before some time ago and, yes, I intially disregarded it, thinking “this can’t be me; I’m really not that bright” (for a discussion addressing this very classic niggle, listen to the podcast “But I’m not really THAT smart” on Embracing Intensity). Thinking such thoughts can loose us a lot of headway in getting to know ourselves and what we are truly dealing with!

The second stumbling block is a strong negativity bias towards the very word “gifted”. This word has been attached to negative connotations such as “being different” or “a-typical” and people feel anxious around such ideas, especially as applied to their child, who they desperately want to “fit in” and “be like all the others”. Thus the degree of negativity applied to the word “gifted”, which is like an unspoken warning not to use the word or risk being accused of elitism, becomes a sort of gaslighting tactic, preventing those with gifts from coming forwards (or seeking help).

In particular, I have hit upon a massive cultural bias towards using the word “gifted”in the UK (where information on the topic is almost nonexistent). I was already feeling thoroughly bewildered by a lack of conversation or community around adult 2Es over here when I chanced upon a post by 2E parent and blogger at Life, Love, Learn, Lucinda: “Why Being British Stopped Me Finding Help For My Twice-Exceptional Child”. All the support groups I have so-far found are in the US, which left me feeling (as ever) a fish out of water when I joined them, well-meaning as they are but there is always that cultural gap. So, where are my nearby tribe of 2E adults, where are all the British blogs, the UK-based podcasts, the local communities, the real-time support? Nowhere to be seen.

When you self-identify with a set of traits, especially traits that have isolated you for a lot to years, its only natural to notice feelings of optimism rise up along the lines of “perhaps now, at last, I will find my tribe of relatable people”. Yet, having plunged the material with great gusto, including a couple of patreon communities, I was starting to feel rather jaded by an absence of cultural fit or locality. Lucinda addresses this conundrum head-on by explaining the term 2E is not really used in the UK (our version, DME or “dual or multiple exceptionality”, is still hardly used…) and that, she says, is because there is a strong bias against labelling a person “gifted” in the UK, as though it smacks of “elitism”. As soon as she explained this (corroborated by a specialist in gifted education that moved from the Netherlands to the UK and found the same brick-wall reluctance, even hostility, towards the word “gifted” over here when she mentioned it to parents) the penny really dropped for me, because I have experienced these anti-giftedness attitudes for myself during the course of my whole life, and in more than one context.

Nobody, and I mean nobody, was called gifted in my schools and, if they had been, they would likely have been treated pretty roughly, not only but their age peers but by some of the members of staff that I can still bring vividly to mind, who seemed to detest and thus bring down to size any child that was different, even in a positive way such as through ability. Even in my family, I realise, there was a very fine line between doing well and seeming exceptional at something, to the degree that I would feel subtly “cautioned”, “put on notice” or even “chastised” if it ever came up, like I was “getting too big for my boots”. In hindsight, I suspect both my parents carried a lot of fear around being seen to be “too different”, risking that you would get targeted by the mob, so I continued to walk that very fine line of doing just enough but not excelling too much (exaggerated by my own deep-rooted fear of drawing attention to myself or my differences, having already been bullied such a lot by an early age). The result was that I languished in this middle territory for a lot of years, too-ing and fro-ing between the will to succeed yet the passionate desire not to be seen or singled out, until I utterly burned-out from the effort and confusion of it all in my mid 30s.

Two major factors that make 2E such fertile territory to explore for anyone who may have an inkling it applies to them (and if they can get over the sticking point of using that word “gifted” for long enough to even consider it) are these:

One is that giftedness often coincides with a trait known as having “over-excitabilities” (which come in many forms, and may not be as obvious as you would think). These fit so closely with many of the highly-sensitive, sensorily over-excitable or even excitotoxic physical symptoms, overly-empathic traits (from extremely over-active mirror neurones!) and ADHD-like traits I have previously explored in this blog over the last number of years. Research suggests that OEs are not only found in the highly able, nor do all highly able individual have OEs of course, but where OEs are present, they are usually much more intense in the highly able. In fact, they have so long been associated with giftedness that they have frequently been considered as a factor for inclusion on the giftedness assessment itself. More on what those over-excitabilities look like in a moment.

The other factor of interest is that, when a person has both giftedness and undiagnosed “deficits” or challenges, the two can appear to cancel each other out, resulting in that person seeming deceptively mediocre, average or kind-of vanilla compared to some of the more obvious high achievers or strugglers, which has been the story of my life. I was either exceptional at something or really struggling internally, and seldom anything “in the middle”, for many of my school years and so, to the casual observer, I often appeared neither one thing or the other. This is because the 2E child can have compensatory skills that mask, say, their ADHD struggles, as I know was the case for me.

For instance, I built a highly complex infrastructure of visual-learning and other “life hacks” that got me through the various executive functioning demands of school, and through exam revision etc. so I could get good grades (even though I noticed how I learned differently to my peers and had to get around this on my own), as well as the mounting pressures of my social and working life as I matured; the trouble being that this took up so much extra effort, energy and time that it all contributed to my eventual burnout. Yes, the homework might appear exceptional but did anyone ever ask how long it took me (is just one example). Very often, the sign of a 2E individual is that they are that person who was once noted for their abilities but who failed to live up to their potential and this is because they are spread so thinly as life makes more and more demands that drain their resources away from their natural talents. They are using everything they have got just to keep up with the appearance of “normal” whilst having the meltdowns at home or inside their own head.

In some skills, they are way ahead yet in others they are extremely undeveloped or behind; perhaps a mini-adult in one department yet with the emotional or sensory processing of a young child in others (asynchronous development). To quote Nicole A Tetreault (Insight Into a Bright Mind: A Neuroscientist’s Personal Stories of Unique Thinking) “Because of asynchrony of the brain and body development, the path for a bright child is an unchartered one and a struggling child may be how a gfted child presents in their giftedness”. I want to add some other food for thought here; how likely might this “struggle” present as pain, even chronic pain, born of isolation, lack of support or of being accepted or understood. Again from Tetreault: “Specifically, social isolation activates the pain centers of the brain as physical pain has a signiture in the brain, pain regardless of the source activates the same brain pathways. Simply put, pain is pain”. I ask this question from the perspective of two decades plus of chronic “mystery” pain in my own life but, if I’m honest, pain niggles going way back to a childhood where I felt caught in a catch-22…when I was my quirky, bright, intense and inspired self, other kids disliked or were suspicious of my oddities and abilities and, when I tried to be more like them, I floundered beneath the kind of struggles and disadvantages that no teacher or parent ever seemed to notice and for which my abilities were no longer a compensation, since I became deeply ashamed of them. In short, my gifts felt like a source of isolation (thus pain) and their primary benefit was to help me disguise myself as more typical than I really was!

When all you want is to fit in, being more able, aware or ahead in certain areas is the one thing you feel compelled to tone down or squirrel away and, in fact, all you ever really do with those skills is use them to survive inspite of having certain defecits, as well as for strategising your attempted assimilation with others (such as studying “typical” behaviours so you can mirror them, deflecting attention and camouflaging yourself). In short, “because of the array of misunderstandings, gifted persons tend to experience social isolation and exclusion” (Tetreault). The effect of isolation and exclusion is to cause lasting trauma that can play out throughout an individual’s life, perhaps not coming to a head until decades later, as happened for me.

Such kids may get off to a fairly good start, even ahead of their peers, but that track-record can start to slip as life gets more demanding and adulthood beckons, as also surely happened to me. One thing that can occur is that the gifted child gets used to things coming easier to them than their peers in the early years…so there they are, reading through great-big-thick adult books at a very early age or acing their hyperfocus topics because they obsess about them or have natural ability in a certain area, but then their peers catch up through hard work, repetition, being better at the stategy game of passing exams or by responding (with less risk of burnout) to all the mounting pressure. So the 2E child can become jaded by the fact that they are no longer finding it quite so easy to shine (thus they start to doubt themselves), plus their peers grow ever-stronger in the executive functions and social skills that they may lack (and which are prized as much, if not more so, in adult life). I was particularly strong in areas that required sensitivity or emotional intelligence, such as literature, history or philosophy, but demand for these skills lapsed, especially as strict criteria for conforming to a particular curiculum or departmental hypothesis of the moment (versus being individualistic or innovative) started to determine the kind of grades available in higher education.

The gifted individual can then start to feel that the very abilities that were most prized or remarked upon in their earlier school years are no longer valued or noticed, may even be despised, when they move out into the world of work. Let’s also remember, as above, that giftedness may not come in the form of adacdemically measurable abilities and that, whilst some other kinds of giftedness (such as emotional intelligence, sensory processing or elevated responses to the environment) may attract interest or hold currency in a younger child, our society tends to value or notice them less in a mature person and such an individual can start to feel as though they slip through the cracks into obscurity as “the only things that matter” now seem to be achievement, output, success and performance.

As though all of that wasn’t quite enough, if that 2E individual has any of the overexcitable traits listed in this post (below) they may also be dealing with far more distraction than a neurotypical peer, parent or teacher could ever imagine, as their everyday baseline of so-called “normal”. For me, that includes sensory perception differences that have been intense, distracting and fairly profound all of my life. I had no idea until very recently that sensory perception differences could have anything to do with giftedness, although I had come across them as a factor in neurodiversity (which giftedness, effectively, is): “While all individuals demonstrate some idiosyncrasy in sensory perception networks, these differences are felt much more in neurodivergent populations such as gifted individuals (Liu et al., 2007; Luders et al., 2009; Thompson & Oehlert, 2010)” (The Gifted Brain Revealed Unraveling the Neuroscience of the Bright Experience – Tetreault).

Perhaps the worst part is not being noticed for all the extra effort it takes to keep a head above water…and the constant struggle…so that 2E individual may start out life feeling gifted and end up feeling disabled or even mentally ill, burnt out and struggling, which I can relate to (though it feels like it has more to do with the fact “life” is not currently set-up to support neurodiversity than anything to do with it being a defecit). Recalling a post I shared recently on my many paradoxical traits (I so often feel as though straddled across a wide gulf of extreme opposite traits, preferences, needs and symptoms), the effect of being gifted in some areas and yet held back in others can make a person seem as though they are coping when they really aren’t, and it can also deprive them of the help, accommodations, understanding or allowances they desperately need for their deficit areas, as well as the recognition they deserve for their exceptionality!

So, what do these overexcitabilities consist of (note, they are not all neccessarily present in the same individual although they can often overlap)? Well, they were grouped into five main areas by Polish psychologist/psychiatrist Kazimierz Dabrowski (a name you will come across a great deal if you research into this topic). Dabrowski devised the Theory of Positive Disintegration, which reminds me of a premise I have worked to for many years now, being that every single thing that has ever looked like it is breaking down in my life, including my health, has ultimately proved to be a positive or, you could say “evolutionary”, in the long run (a version of “whatever doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger”). I have held vehemently to this optimistic outlook all of my life, such that it appears to be an intrinsic part of my wiring, keeping my mindset open, curious and opportunist even when things get most demoralising and demanding.

His five areas of OE, in brief, are as follows:

Psychomotor – a constant need to move and expend intense physical energy. Kids with psychomotor overexcitability have drive, are impulsive, and often show a physical manifestation of their emotions. They may also have nervous habits or tics, and may have trouble sleeping. I know I learned to keep mine closely in check as a child, so as not to attract attention (except when freely running around outdoors, which was highly essential to my wellbeing, and I have always had taps, twiches and other “stims”) but as an adult, dance has been a near-essential part of my everyday life with times when I haven’t indulged in this marked by ever-worsening health. These days, I take regular dance “breaks” throughout the day and they work to regulate my emotions as well as to keep my creative and intellectual energy moving. This is the category that can look most like the idea of ADHD and yet there is more to it than that (and, put with some of the next areas of OEs, there is certainly no “deficit” of attention here). If accommodated, the need to move the body can be an outlet for pent-up emotions or even a gift that helps inspiration come through with better flow but, very often, non-accommodating styles of teaching and classroom (or office) arrangement and the cultural idea of what constitutes “appropriate adult behaviour” chip away at this need to move as the individual matures, creating more and more problems as a result of reduced outlets in adult life (something which had a devastating effect on my health for a long time, until I realised I felt like a pressure cooker inside without regular bursts of movement).

Sensual – a heightened awareness of all five senses – sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste. It can included oversensitivity to the textures of food, to certain fabrics, clothing tags and so on, an exagerated startle response and a dislike of being touched in a certain way, or at all. Articles on this category of OEs tend to miss out, in my opinion, the extra-sensory excitability that can lead to those susceptible noticing less typical stimuli such as changes in air pressure, manmade or natural EMFs in the environment, geomagnetic variables caused by geography and the sun, the magnetic influence of the moon cycle, even our over-active mirror neurones picking up on the moods and emotions of other people in the vicinity, all of which I have talked about experiencing many times before (and which, for most people, are incomprehensible “sensitivities” although, for me, they are very real and present in my life). Basically, a person with sensual OEs responds to stimuli to a much greater degree than other people and those sensations can be highly distracting, lifestyle encroaching or even the root of chronic health issues and pain (spoken from experience). Their world comes in at them in a far less filtered way and it can be utterly overwhelming, even before anything else happens in their day. They are quite literally having a different experience to other people around them a lot of the time (which affects relatability, how seriously they are taken and significantly adds to a sense of living in isolation). The Highly Sensitive traits identified by psychologist Elaine Aron most certainly overlap with this type of OE and are talked about a great deal by adults with 2E, although they can be more nuanced and intense for someone dealing with the excitability-giftedness overlap.

Emotional – extreme emotions, anxiety, guilt, sadness, happiness, difficulty adjusting to change. Prone to panic, depression, mood swings, stomach aches, needing more reassurance. They can become consumed with perfectionism, inhibition, introversion, self-evaluation, self-judgement. Also open to peaks of joy and excitement, in fact whatever is felt tends to be experienced intensely, deeply and in a far more all-consuming way that is very hard to explain to a neurotypical individual. Such intense feelings arise that they may “burn” themselves or others around them. When such strength of emotion is harnessed, it becomes a super-power because it adds the all-important ingredient to hyperfocus (see intellectual OE below) necesary to invest them in a task and see it to completion. Because when the individual is emotionally engaged in the area of hyperfocus they readily harness their giftedness, but when they don’t give a damn about the task they have been allocated it can be abject torture to them…or their ability to complete it can fall apart. They can be deeply moral and concerned with right and wrong, prone to worrying about consequences or unintentional harm done to others, worried about others feelings, about injustice, the state of the world, with matters way outside of their control pressing down on them like a dead weight at an early age. They can feel morally seperate from the world because the mainstream world seems to lack compassion or moral values.

Intellectual – highly excited and engaged by activities of the mind, thought, and metacognition and the trait most widely associated with “giftedness”. A deep and relentless curiosity, love of problem-solving, always seem to be thinking, a risk of ruminating, falling down the rabbit hole and tendency to hyperfocus, finding it very hard to put a thinking activity down at the expense of other daily activities or demands. Often have a multi-level perception of reality and can join dots across a variety of disciplines, and diverse situations, spotting analogies, linking macro with micro examples of similar situations, or using metaphors in a way that indicates they are thinking way outside the box (and more like a mind-map!), which can baffle those with a more linear/compartmentalised way of viewing the world. Such an individual takes in so much more than anyone else so, in effect, they experience a whole other reality to everyone else and this can be both profoundly isolating but also a blessed gift, which is another of those paradoxical experiences I keep noticing in myself. In everyday life, it can make their attention feel divided between “this” world and some other world, which can come across as being ungrounded, distracted or dreamy yet it is anything but a lack of attention or intelligence and it can allow them to access information or solutions that elude other people. As above, when they are emotionally invested in their particular area of hyperfocus they can become laser-like in their intellectual ability and this is a real gift.

Imaginal – Imaginations that go to amazing places, even getting carried away or into worst-case scenarios. May have imaginary friends or attribute personalities to toys, animals or inanimate objects. Vivid dreams, a love of music, drama, art etc. May tend to lose themselves, or prefer to dwell in, their imaginary places and take escapism to a whole other level.

“The overexcitabilities (OEs) may be thought of as an abundance of physical energy, heightened acuity of the senses, vivid imagination, intellectual curiosity and drive, and a deep capacity to care. Individuals may experience one or more of these OEs at varying degrees of intensity. The greater the strength of the OEs, the greater the developmental potential for following an ethical, compassionate path in adulthood” (Lysy & Piechowski. 1983; Piechowski, 1979).

I can relate, and offer personal examples, of all the above caegories. One other factor I feel needs underlining, twice, is that 2E individuals are often intense, and I mean really INTENSE…both in terms of what they are experiencing for themselves (compared to how other people experience life) and how they come across to other people. This can be a major challenge for all concerned and, again, may contribute to a sense of isolation if it impacts the longevity of relationships (or whether they are even formed in the first place). Many 2E individuals reach the conclusion they are “too much” for most people to handle, so they either withdraw completely or make themselves smaller in an attempt not to offend or take up space (whilst assuming they, with their differences, are always the one “to blame” when friendships fall apart).

Going back to Lucinda’s post, she identifies three areas that, when they overlap, can create a sort of perfect storm of issues for a 2E child as they develop, not least because, with them, they somehow fall through the cracks of the prevailing criteria for identifying giftedness in our schools. These are:

(1) socio-economic factors stashed “against” such kids (such as low-budget schooling, no quiet space or support at home to “grow” talents or explore deficits, poor schooling, strong negativity bias in certain families/communities against being perceived as special or different, etc.) (ii) having unidentified learning disabilities and iii) having high levels of over-excitabilities.

I realise, with a loud bell going off, that I had all of these three things “against” me and subsequently fell down those cracks, especially in adulthood (after they had done their damage during my schooling years) because all I had learned to do, very well, was seem OK whilst hiding all the ways that I struggled…a state of affairs that was not going to be sustainable in my adult years, thus it was a timebomb waiting to go off. To be honest, I am impressed I held it together until my 30s before having that burn-out. All this, because neither giftedness nor deficit were picked up when I was developing.

In my highly overcrowded household whilst growing up, in which I was the much younger child that barely fit in with all the noisy adolescents crammed into our miniscule house, I learned very quickly that it was best to disappear into the cracks and not take up space. There was an almost complete absence of one-to-one attention, room for or acceptance of, my very highly over-sensitive nervous system in such a rumbustious household during my early developmental years and my schooling certainly lacked the means to identify any deficits or gifts. In both scenarios, I did my level best to slot in and attract as little attention as possible. Yes, I did well in some areas but I also struggled, profoundly, in ways that I now relate to as unaddressed autism and ADHD…and nobody knew about those so I took up all the slack myself, as best I could, whilst working hard not to draw attention to myself.

Worst of all was a high degree of over-excitability (especially sensorily, intellectually and in my imagination) that I assumed to be normal but which vastly altered the intensity and depth of perception that went into (continues to go into…) all of my everyday experiences; a profound difference of perception that I only somewhat grasp the magnitude of now as I start to learn about my neurodiversity as a mature adult. My long-running assumptions that any of this is normal or relatable to others have been well off the mark for years and have only contributed to a deep sense of isolation when others have failed to identify with my experiences and challenges. To this day, I struggle to come to terms with how many of my normal everyday experiences remain beyond the comprehension of those I would love to form a closer, more relatable raport with. Though I can often meet them where they are, most people seem to struggle to relate to the depth and complexity of my sensory or emotional perception of “the world” or my desire to think so deeply into all of my subjective experiences as a top priority of my life (and as a means of navigating my unique sense of purpose in this world). My primary fixations seem to leave many people bewildered or “cold” (just as theirs, frequently seem shallow, trivial and without individuality) or, to put it another way, they often don’t have a single clue what I am “going on about”and this can be hard to live with; I think we all crave people to relate to and who can relate to us as part of the human condition. “Gifted individuals often report feeling significantly different to their neurotypical peers (Rinn & Majority, 2018; Fonseca, 2015; Bernhardt & Singer, 2012)” (The Gifted Brain Revealed Unraveling the Neuroscience of the Bright Experience – Tetreault).

On the other side of the coin, a child growing up with 2E in an environment that absorbs their traits, as in, they are met “exactly as they are” and not treated, measured or shown-up to be any different by that environment, may not show up as 2E because they are doing sort-of alright. In other words, the very fact of having traits flag up can be a kind-of benchmark of where the traits do not fit the environment, and vice versa (which is why they can show up more in some phases of a person’s life than another). I can certainly see that, for all I found my homelife highly overstimulating while my siblings lived at home, there was a level at which I didn’t even notice my own struggle in that environment because we were all a bit neurodiverse and oddly fixated (compared to other people) so this, for me, was normal. (Some of my family have done rather better out of their quirky fixations, turning them into areas of academic specialism and progression, such as a forging a career in “black holes”, as one example, but I never seemed to turn my niches into something of practical application except, perhaps, via my art.) So, within my family, I pass off as one of a kind and it remains easier to be myself, without such a strong sense of defecit coming to the surface.

It has really been the outside life of early school days, work and (particularly) adult friendships that have thrown me way off-kilter (a challenge that continues today, if I am ever forced to step outside of the carefully guarded “neurodivergent” world I have created with my a-typical partner). Things went haywire, above all, in my young-adult life and, later, in a corporate working environment (compared to my adolescence, which was tolerable once my siblings left home, which effectively turned me into an only child at home with my retired parents plus I was, by then, doing alright at school, with my coping mechanisms and my small niche of quirky friends in place). As a result, my 2E status has only showed up the more as life has increased its frictions and its challenges.

Those late teenage years were the era when I “shone” the most brightly at school because I had my coping mechanisms in place and could put all my energy into holding things together in my self-devised way (and the very fact I devised such a well-oiled structure of self-supporting, self-soothing and self-camouflaging behaviours to hide my intense emotional struggles and learning differences at that age is testament to a kind of giftedness; however they didn’t outlast the rigors of the university years nor, especially, the giant step-up to going out to “work” ). When my college urged me to apply for “Oxbridge” (Oxford and Cambridge universities) I knew that was a step too far because I felt like an intellectual fraud and as though my systems for performing according to “normal” accademic expectations were too flimsey to be tested (and, in a sense, they were as I had had to teach myself how to learn and perform to methods that were not inherently my own and, thus, felt wrong footed). In other words, I felt like an imposter in a neurotypical world, a feeling that haunted me in every walk of life there onwards and which is, apparently, very common amongst 2E individuals.

I still live with profound over-excitabilities, as well as peaks of exceptionality, but I have learned how to manage the see-saw rather better (the hard way) using various techniques and life hacks (see my last post), including self-awareness and the invaluable tool of journalling my experiences and feelings as they arise in order to better understand them. However, back then, I had no such support; a realisation that can hit you rather hard in hindsight, not least when you hear about the kind of support that at least some (sadly not all…) children are receiving for twice-exceptionality today. Part of the necessary process of coming to realise your own neurodiversity, in all its forms, as a mature adult is to mourn for the child that you once were and to offer to yourself the recognition and support that you never received. All these feelings of profound sadness, along with the arising self-recognition of your own traits and hardships, have to be allowed up and out of yourself in order to bring about the coming-to-terms part that leads to a whole different way of coinciding with your own unique “wiring”, whereby you can start to love and appreciate the glitchy way you are made. You have to work through the trauma of never having understood this thing about yourself until now and get yourself to the other side of that, to reap the benefits of hindsight and move onwards.

Back then, I became so convinced (at some subliminal level) that to expose either my gifts or my deficits was to guarantee relentless persecution that I spent decades hiding them away, camouflaging and portraying myself as vanilla or average in an almost bloody-minded pursuit of invisibility, along with the very-real factor that my unrecognised and often profound sensory, executive and other challenges literally did cancel out areas where I might have shone with my giftedness.

The new realisation that 2E status is simply not spoken about or embraced willingly in the UK has been HUGE to understand in retrospect because, following my own lifetime of issues, I then had to navigate the same thing, all over again, when my daughter went through school; yes, put onto the gifted register, for what that was worth, but the other side of that same coin, where she really struggled with over-excitabilities, was never noticed or believed at school so I was on my own as history started repeating itself. This, inevitably, raked up a lot of my own childhood trauma around being invisible, misunderstood, unsupported and shut down because of my differences. Without the input of 2 particular teachers (one of whom has an autistic daughter) who accepted her struggles alongside her giftedness and worked with me, instead of treating me (as was far more typical!) as the “neurotic, overly-concerned parent seeking special treatment for my child” when I indicated things were not nearly as plain sailing as they seemed on the surface, things may have turned out very differently. In the UK, having such teachers on board with your child’s 2E traits is about the only thing you can hope for (or the possibility of home schooling) according to Lucinda, which is so sad to hear. I really hope that kids coming through now get the understanding and support that was missing during my experiences of school and that our cultural stuck-point over the concept of “giftedness” can be put behind us all so that far less children fall through the cracks.

What is gifted, really, and can it apply to me (you may still be asking)? Well, if you are still reading this then I suggest that you may very well be gifted because you would have lost all interest or sense of relating to what I am sharing long ago, if not. In fact, according to one professional who assesses 2E traits for a living (interviewed in one of the countless podcasts I have now listened to on this topic), not one adult that has come to her for assessment, wondering if they are gifted, has ever turned out not to be gifted; in fact, the very trait of pushing so hard to understand “what went wrong for me” or “why do I feel so different” is a sign of gifted traits because we are the type that asks such big questions and never tires of searching for answers to make sense of our almost unfathomable complexity. We often possess great tenacity and we never, ever, stop searching for those answers and clues to our own struggles, yet we also play down our own gifts and assume we are no more exceptional, or deeply aware, than the next person (even with all the many signs to the contrary). On the other side of the coin, there is great risk to over-favouring the idea of giftedness without also addressing any deficits because to do so would not get you any of the support you may need with, say, ADHD (which cannot simply be ignored) so you have to take in the whole picture to get somewhere with all this and make a super-power of it. A 2E individual is sat on a precarious see-saw and both sides need to be balanced in the middle for a less bumpy ride, as many of us have come to know the hard way…often long before we trip upon the very concept of being 2E.

If this sounds like you or someone in your care, I suggest you pick up from here and explore for yourself, with a few resources suggested below. When we start to develop broader (less defecit oriented) ways of looking at these cross-over traits than is currently dictated by the DSM, neither shunning (nor limiting our definition of) that word “gifted” as we have done in the past, we will really start to get somewhere, so I suggest you look at the concept of giftedness again, through fresh eyes, to incorporate some of the traits and clues I have mentioned above. With the right support, and more understanding, we can come at them at a higher level, ready to navigate the challenges and gifts with far more adriotness and acceptance. From my own experience, you can then start to experience your own intensity from the point of view of knowing where it stems from (no more talk of being “broken”!) and thus you can make far more headway with developing the tactics of emotional regulation and sensory buffering, not to mention excutive hacks and other tools that you need to get through your unique version of an average day in a far more comfortable, (positively) driven and inspired way. Knowing how to work with your own quite unique nervous system, recognising what triggers the stress cycles and how to work through that stress, paired with understanding what your sensory preferences are, is really important and it is close self-observation (plus a degree of trial and error) that will get you there, once you are much more fully aware of both your incredible strengths and your considerable challenges, in equal proportion.

Resources:

Embracing Intensity podcast

Embracing Intensity website and patreon community

Third Factor resources and patreon community on the topic of over-excitability

Gifted, Talented and Creative Adults

Laugh, Love, Learn (a blog about life in a sensitive, intense family)

Overexcitability and the Gifted article, Sharon Lind

The Moral Sensitivity of Gifted Children and the Evolution of Society – article, Linda K Silverman

Leah K Walsh – Creating a Culture for Sensitive People to Thrive

Insight Into a Bright Mind: A Neuroscientist’s Personal Stories of Unique Thinking – excellent book by Nicole A. Tetreault

The Gifted Brain Revealed Unraveling the Neuroscience of the Bright Experience – Nicole A. Tetreault.

thank you so much

LikeLiked by 1 person